by Colby Russell. 2021 February 13.

If I don't have the time budget to Do The Thing, it doesn't make sense for you

to assume that the budget exists to have a conversation about Doing The

Thing, where I describe how I would do it if I did have the time.

(This shouldn't be difficult to understand. Think about the amount of time

each would take. If the cost of the latter is the same or greater than the

cost of former, then...?)

This seems pretty basic to the point that I'd think it should go without

saying. It's abundantly, frustratingly clear to me, though, that for some

people, it does need saying—which of course is a problem, since there is no

time for it.

Hopefully this explanation helps. Most likely, though? It won't.

by Colby Russell. 2020 December 7.

Here's a new rule for technical discussions: any time someone introduces a

metaphor or analogy, it ends with them—that is, the analogy is only in

play for the duration of the message where it is first introduced. If you

engage the point being made by trying to build upon the analogy or recast it

with some tweaks in order to make a counterpoint, then you automatically lose.

(In a truth-seeking discussion, this amounts to forfeiting your attempt and

being obligated to try again.) The game of "strain the analogy" is neither

useful nor fun.

by Colby Russell. 2020 May 14.

JavaScript is a programming language. NodeJS is not. It's the substrate that

the NPM ecosystem runs on.

The kneejerk comment from the JS hater you're responding to may not have been

made with that distinction in mind, but a distinction exists.

It's very much a possibility that the JS hater uses Firefox. Firefox is

implemented using an Emacs-like architecture. The Firefox codebase includes

millions of lines of JS, and that's been the case since before the language

was JITted. For Firefox 1.0, 2.5, and 2.0, I used to run it every day on an

800MHz PIII with 128 MB (later 192 MB, wow-wee!) of RAM. The JS in the

Firefox codebase wasn't written in the NodeJS style, and if it had been, that

would have made it a non-starter.

Kneejerk JS haters are tiring, but so is the complicitness of NodeJS advocates

in conflating JS with the NodeJS ecosystem.

by Colby Russell. 2020 May 13.

If you have a wiki and in your contributor instructions you say to:

- Fork the repository

- Create a new branch for your changes

- Edit or add the markdown file for the page that you want to change

- Commit with an appropriate message

- Submit a PR

... then you don't have a wiki.

by Colby Russell. 2020 May 10.

(I'm including below two

entries from my paper journal from 2015.)

2015 March 12

One of the worst parts about trying to introduce yourself to the source of a

new project is grappling with the source layout. I think I've struck upon an

approach to dealing with this.

I propose two new tags for documentation generators: @location and @index.

@location should be used to explain why a file is where it is. To be used

judiciously. (I'm hesitant to say "sparingly", since that's usually taken to

mean "don't use this", and that's not what I mean.)

@index can be used to document the source tree layout. We have

@fileoverview, but that does little to explain the rationale behind

directory structure. Use @index within a single file within a directory to

delegate this responsibility to that file. Can be combined with @location

or @fileoverview.

2015 May 17

I'd like a source code inspector.

I wrote on 2015 March 12 about some extensions to javadoc-/doxygen-style

annotation schemes, to explain how @location and @index tags could used to

better document codebases.

Specifically, the problem I'm referring to is this: I get a link to a repo

and am presented with a file tree and sometimes a README. The README is

sometimes helpful, sometimes not. When I'm digging through the source tree in

either case, what's not helpful is the three-column table presentation of

$DIRECTORY_OR_FILE_NAME, $RECENT_COMMIT_MESSAGE, $RECENT_COMMIT_DATE,

where the commit is the one that last changed that particular file/directory.

(Really, I have no idea why this is so prevalent in web-based version control

frontends. It seems like it has to be a case of, "Well, this is just what

these sorts of things always look like...", without regard for whether it's

helpful or if it ever made any sense at all.)

What I'd like to see in its place is a one-liner for each entry in the file

tree, to describe the source layout. This is harder to do for directories,

which is why I proposed @location and @index.

@index + @fileoverview associates the annotations for the file containing

them with the directory that the file appears in, in addition to the file

itself.

@index + @location can be used if the file's @location annotation is a

good way to describe the parent directory.

Uncombined @index with argtext of its own can be used where neither the

file's own @location nor its @fileoverview are good candidates for

describing the parent directory.

[For @index-as-a-modifier, it should either appear on the same line as the

associated @location or @fileoverview tag, or it can appear on a line by

itself, with no argtext of its own, in which case it modifies whatever tagspec

preceded it.]

I'm also considering the idea of using a filename argument to the @index

annotation, for deferring to some other file like so:

@index README.markdown—where the README could contain a source layout

section to describe things. E.g.:

== Source layout ==

@index README.markdown

* foo/ - Short description of foo/ goes here...

* bar/ - Description of baz/

* baz/ - likewise...

'@index. ' could be used as shorthand, so repeating the

name of the file isn't necessary, and would guard against file moves.

Sophisticated markdown viewers could hide the tag and/or turn the directory

labels into live links. NB: The two trailing spaces at the end when @index

is used this way (i.e. inside a markdown file) MUST be included; the

treatment of LF/CRLF in GitHub-flavored markdown is a sin.

[To distinguish between the argtext-as-description and argtext-as-delegate for

@index, the rule would be "If it looks like a file name, then it's a file,

otherwise it's freeform text". ("Looks like a file name" isn't as hard as it

sounds; the contents of a given directory are knowable/known.)]

by Colby Russell. 2019 May 15.

In February, I mentioned that I would be adopting a writing regimen where I

publish all material on any subject I've given thought to writing up that

month, and to do so regardless of whether I've actually sat down and finished

a "proper" writeup for it.

What's the point of something like this? It's like continuous integration for

the stuff in your head. For example, the faster binaries nugget included here

in this brain dump is something I'm able to trace back to a thought I'd

sketched out on paper back in April 2015, and even then I included a comment

to myself about how at the time I thought I'd already had it written down

somewhere else, but had been unable to find it.

This is inspired in part by Nadia Egbhal's "Things that happened in

$MONTH" newsletter, but the subject matter is more closely aligned

with samsquire's One Hundred Ideas For Computing.

Having said that all that, I didn't actually end up doing anything like this

for March or April, due to a car accident. But here is this month's.

Sundry subdirectories

When working on software projects, I used to keep a p/ directory in the repo

root and add it to .git/info/exclude. It's a great way to dump a lot of

stuff specific to you and your machine into the project subtree without

junking up the output of git status or the risk of accidentally committing

something you didn't need to. (You don't want to use .gitignore because

it's usually version-controlled.)

I had a realization a while back that I could rename these p/ directories to

.../, and I've been working that like for several months now. I like this a

lot better, both because it will be hidden in the directory listings (just

like . and ..), and because the ellipsis's natural language connotations

of being associated with "sundry" items. It feels right. And I have to

admit, p/ was pretty arbitrary. I only picked it because it was unlikely to

clash with any top-level directory in anything I clone, and because it's

short. ("p" stood for "personal".)

Aspirational CVs

Here's an idea for a trend:

Fictional CVs as a way to signal the kinds of things you'd like to work on.

Jane is churning out React/whatever frontend work for her employer or clients.

What she'd like to be doing is something more fulfilling. She's interested in

machine learning, and she's maybe even started on a side project that she

spends some personal time on, but she's often tired or burnt out and doesn't

get to work as much on it as she'd like.

So one day when Jane is frustrated with work and has her thoughts particularly

deep in chasing some daytime fantasy about getting paid to do something closer

to her heart's desire, she cranks out an aspirational CV. Mostly therapeutic,

but partly in the hopes that it will somehow enable her to actually go work on

something like she describes in CV the entry.

In her aspirational CV, Jane writes from a far future perspective, where at

some point in the not-too-distant future (relative to present day), she ran

into an opportunity to switch onto the track in her career that turned out to

be the start of the happiest she's ever been in her professional life. The

fictional CV entry briefly summarizes her role and her accomplishments on that

fantasy team, as well as a sort of indicator of a timeline where she was in

that position.

Two weeks later, back in the real world, someone in Jane's company emails her

to say they saw her aspirational CV that she posted on social media. They

checked out her side project, too, and they want to know if she'd be available

to chat about a transfer to work on a new project for a team that's getting

put together.

Software finishing

I like sometimes in fiction where they present a plausible version of the

world we live in, but it differs just slightly in some quaint or convenient

way.

It's now widely recognized that global IT infrastructure often depends on

software that is underfunded or even has no maintainer at all. Consider,

though, the case of a software project whose development activity tapers off

because it has reached a state of being "finished".

Maybe in an alternate universe there exists an organization—or some sort of

loosely connected movement—that focuses on software comprehensibility as a

gift to the world and for future generations. The idea is that once software

approaches doneness, the org would pour effort into fastidiously eliminating

hacks around the codebase in lieu of rewrites that presents the affected logic

in a way that's clearer. This work would extend to getting compiler changes

upstream that allows the group to judiciously cull constructs of dubious readability so

that they may be replaced with such passages, which may have previously been

not as performant but that now work just as well as the sections being

replaced, without any penalty at runtime.

For example, one of the cornerstones of the FSF/GNU philosophy is that it

focuses on maximizing benefit to the user. What could be more beneficial to

a user of free software than ensuring that its codebase is clean and

comprehensible for study and modification?

Free software is not enough

In the spirit of Why Open Source Misses The Point Of Free Software, as well

as a restatement of Adam Spitz's Open Source Is Not Enough—but this time

without the problematic use of the phrase "open source" that might be a red

herring and cause someone who's not paying attention to mistake it for trying

to make the same point as Stallman in the former essay.

Free software is not even enough.

Consider the case of some bona fide spyware that ships on your machine, except

it's licensed as GPLv3. It meets the FSF's criteria for the definition of

free software, but is it? You wouldn't mistake this for being software that's

especially concerned for the user.

Now consider the case of a widely used software project, released under a

public domain-alike license, by a single maintainer who works on it unpaid as

a labor of love, except its codebase is completely incomprehensible to anyone

except the original maintainer. Or maybe no one can seem to get it to build,

not for lack of trying but just due to sheer esotericism. It meets the

definition of free software, but how useful is it to the user if it doesn't

already do what they want it to, and they have no way to make it do so?

Related reading:

"Sourceware" revisited

The software development world need a term for software with publicly

disclosed source code.

We're at this weird point, 20 years out from when the term "open source" was

minted, and there are people young and old who don't realize that it was made

up for a specific purpose and that it has a specific meaning—people are

extrapolating their (sometimes incorrect) misunderstandings just based on what

the words "open" and "source" mean.

That's a shame, because it means that open source loses, and we lose "open

source" (as useful term of art).

The terms "source available" and "shared source" have been available (no pun

intended), but don't see much use, even by those organizations using that

model, which distressingly sometimes ends up being referred to as "open

source" when it's not.

For lack of a better term, I'll point to the first candidate that the group

who ultimately settled on "open source" first considered: "sourceware". That

is, used here to refer to software that is distributed as source, regardless

of what kind of license is actually attached to it and what rights it confers

to recipients. If it's published in source code form, then it's sourceware.

The idea is to give us something like what we have in the Chomsky hierarchy

for languages.

So we get a Venn diagram is of the nested form.

- sourceware is the outermost set

- free/libre/open source is nested within that

- copyleft is within that

... additionally, continuing the thought from above (in "Free software is not

enough"), we probably need to go one step deeper for something that also

incorporates Balkan's thoughts on the human experience in ethical design.

Changeblog

Configuration as code can't capture everything. DNS hosts are notorious for

every service having their own bespoke control panel to manage records, for

example.

In other engineering disciplines outside of Silicon Valley-dominated / GitHub

cowboy coder software development, checklists and paper trails play an

important role.

So when you make a change, let's say to a piece of infrastructure, and that

change is not able to captured in source control, log a natural language

description of the changes that were made. Or, if that's too difficult, you

could consider maintaining a microblog written from first person perspective

of (say) the website that's undergoing changes.

"Oh boy, I'm getting switched over to be hosted on Keybase instead of

Neocities."

Orthogonally engineered REST APIs

Sometimes web hosts add a special REST API. You probably don't need to do

this! If the types of sites you're hosting are non-dynamic sites, it would

suffice if you were to implement HTTP fully and consistently.

For an example (of a project that I like): Neocities uses special endpoints

for its API. If I want to add a file, I can POST a JSON payload, encoding the

path and the file contents, to the /api/upload endpoint.

But if my site is example.neocities.org and I want to upload a new file

foo/bar.png, the first choice available to me should be an HTTP PUT for

example.neocities.org/foo/bar.png. No site-specific API required.

Similarly for HTTP DELETE. HTTP also has support for a "list" operation—by

way of WebDAV (which is a part of HTTP), which Neocities already supports.

I shouldn't need to mention here that having a separate WebDAV endpoint from

the "main" public-facing webserver isn't necessary either. But I've seen a

lot of places do this, too.

These changes all work for sites like Neocities, because there is a

well-defined payloads and namespace mapping, although it doesn't necessarily

work as well for a site like Glitch which allows arbitrary user code to

register itself to act as handler code on the server (but if the user's Glitch

project is a static site known not to have its own request handling code in

the form of a NodeJS script activated by package.json, then why not!)

Also could work for hashbase.io and keybase.pub, so long they pass along

enough metadata in the request headers to prove that the content was signed by

the keyholder. In the case of Hashbase, it'd be something similar to but not

the same as Authorization: Bearer header, except with the header value

encoding some delta for the server to derive a new view of the dat's Merkle

tree. In the case of keybase.pub, whatever kbfs passes along to the Keybase

servers.

You don't need bespoke APIs. (Vanilla) HTTP is your API.

Lessons from hipsterdom applied to the world of computing

I'm half joking here. But only half.

escape.hatch — artisanal devops deployments

People, even developers, are hesitant to pay for software. People pay for

services, though. Sometimes, they won't be willing to pay for services in

instances where they see their payments as an investment and are trepidatious

about whether the business they're handing over money to is actually going to

be around next year. That is, if a service exists for $20 per year, it's not

enough to satisfy someone by giving them 1 year of service in exchange for

$20 in 2019. They want that plus some sort of feeling of security that if

they take you up on what you're selling, then you're going to be around long

enough that they can give you money next year, too (and ideally, the next year

after that, and so on).

People—especially the developer kinds of people—are especially wary of backend

services that aren't open source. Often, they don't want to cut you out and

run their own infrastructure, but they want the option of running their own

infrastructure. They like the idea of being free to do so, even though they

probably never will.

escape.hatch would specialize in artisinal devops deployments. Every month,

you pay them, and in return they send you a sheet of handwritten notes. The

notes contain a private link to a video (screencast) where they check out the

latest version of the backend they specialize in, build it, spin up an

instance on some commodity cloud compute service, and turn everything over to

you. The cloud account is yours, you have its credentials, and it's your

instance to use and abuse. The next month, escape.hatch's devops artisans

will do the same thing. The key here is the handwritten notes and the content

of the video showing off your "handwoven" deployment—like a sort of

certificate.

The artisans will be incentivized to make sure that builds/deployments are as

painless and as easy as possible and also that their services are resource

efficient, because they're only able to take home the difference between what

you pay monthly and what the cloud provider's cut is for running your node.

(Or maybe not, in the case of a plan whose monthly price scales with use.)

Consumers, on the other hand, will be more likely to purchase services because

they reason to themselves after watching the screencasts every month, "I could

do all that, if I really needed to." In reality, although the availability of

this escape hatch makes them feel secure, they will almost definitely never

bother with cancelling the service and taking on the burden of maintenance.

(NB: the .hatch TLD doesn't actually exist)

microblogcasts — small batch podcasts

- like a 5 minute video essay, but it's an audio-only segment (lower

investment to produce) about That Thing You Were Thinking Of At Work Today

And Wanted To Bring Up Later

- way easier to make an off-the-cuff 5-minute recording of your thoughts and

make it available to your social circle than it is to sit down and write a

blog post

- foremost for friends and family

- probably just a replacement for existing conversations you already have

- not private, so much as it is some monologue/soliloquy that you'd spitball

about in person, but not exactly interesting to listen to for people you'd

never speak with in person

- not everyone is interesting

- no one is interesting all the time

- better than texting or otherwise fidgeting with written/visual social media,

because one has to stop to create it; also takes more time and

intentionality to consume than reaching for your phone at the first hint of

idle time and then quickly swiping through things

- different from a phone call, because it's asynchronous and half-duplex;

would feel like it would have the same gravity (and intentionality) as

leaving a voicemail—not just something to do to feel "connected" on your

drive home

- musicians often create hits that they didn't know were going to work out

that way; occasionally ordinary plebs will say something that's much better

received and has a much wider reach than intended or expected because it

ends up reasonating with other people

Improvements to man

I want to be able to trivially read the man pages for a utility packaged in my

system's package repositories, even when that utility is not installed on my

system. I'm probably trying to figure out whether it's going to do what I

need or not; I don't want to install it just to read it and find out that it

doesn't. I don't want to search it out, either.

Additionally, the info/man holy war is stupid. Every piece of software

should have an in-depth info-style guide and and man-like quick

reference. It's annoying to look up the man pages for something only to find

that it's got full chapters, just like it's annoying to find that no man page

exists because the GNU folks "abhor" them.

But I don't want to use the info system to browse the full guide. (It's too

unintuitive for my non-Emacs hands.) I want to read it in the thing I use to

browse stuff. You know―my browser.

Also, Bash should stop squatting on the help keyword. Invoking help

shouldn't be limited to telling me about the shell itself. That should be

reserved for the system-wide help system. C'mon.

Dependency weening

As a project matures, it should gradually replace microdependencies with

vendored code tailored for callers' actual use cases.

Don't give up the benefits of code re-use for bootstrapping. Instead start

out using dependencies as just that: a bootstrapping strategy.

But then gradually shed these dependencies on third-party code as the

project's needs specialize—and you find that the architecture you thought you

needed can maybe be replaced with 20 lines of code that all does something

much simpler. (Bonus: if you find that a module works orthogonally to the way

you need to use it, just reach in and change it, rather than worrying about

getting the changes upstream.)

Requires developers to be more willing to take something into their source

tree and take responsibility for it. The current trends involve programmers

abdicating this reponsibility. (Which exists whether you ignore it or not;

npm-style development doesn't eliminate responsibility, just makes it easier

to pretend it isn't there.)

Programs should get faster overnight

I mean this in a literal sense: programs should get faster overnight. If I'm

working on a program in the afternoon, the compiler's job should be to build

it as quickly as possible. That's it. When I go to sleep, I should be able

to leave my machine on and it's then that a background service uses the idle

CPU to optimize the binary to use fewer cycles. It would even be free to use

otherwise prohibitively heavyweight strategies, like the approach taken by

Stanford's STOKE. When I wake up in the morning, there is a very real

possibility that I find a completely different (but functionally equivalent,

and much faster) binary awaiting me.

In fact, we should start from a state where the first "build" is entirely

unnecessary. The initial executables can all be stored as source code which

is in the first instance fully interpreted (or JITted). Over the lifetime of

my system installation, these would be gradually converted into a more

optimized form resembling the "binaries" we're familiar with today (albeit

even faster). No waiting on compilers (unless you want to, to try moving the

process along), and you can reach in and more easily customize things for your

own needs far more easily than what you have to do today to track down right

source code and try getting it to build.

Self-culling services

tracker-miner-fs is a process that I'll bet most people aren't interested

in. On my machine, a bunch of background Evolution processes are in the

same category. Usually when I do a new system install, I'll uninstall these

sorts of things, unless there's any resistance at all with respect to

complaints from the system package manager about dependencies, in which case I

tend to immediately write it off as not worth the effort, at which point I

decide that I'll just deal with it and move on.

Occasionally, though, when I've got the system monitor open because I'm being

parsimonious about compute time or memory, I'll run into these services again,

sitting there in the process list.

To reiterate: these are part of the default install because it's expected

that they'll be useful to a wide audience, but a service capable of

introspection would be able to realize that despite this optimistic outlook,

I've never used or benefited from its services at all, and therefore there's

no reason for it to continue trying to serve me.

So package maintainer guidelines should be amended to go further than simply

dictating that services like these should be trivially removed with no fuss.

The guidelines should say that such background services are prohibited in the

default install unless they're sufficiently self-reflective. The onus should

be on them to detect if they're going silently unused and then disable or

remove themselves.

Code overlays

Sometimes I resort to printf debugging. Sometimes that's more involved than

the colloquialism lets on—it may involve more than adding single line printf

here and and there; sometimes it requires inserting new control flow

statements, allocating and initializing some storage space, etc. Sometimes

when going back to try and take them out, it's easy to miss them. It's also

tedious to even have to try, rather than just wiping them all out. Source

control is superficially the right tool here, but this is the sort of thing

you're usually doing just prior to actually committing the thing you've been

working on. Even with Git rebase, committing some checkpoint state feels a

little heavyweight for this job.

I'd like some sort of "code overlay" mechanism comprising a standardized

(vendor- and editor-neutral) format used as an alternative to going in and

actually rewriting parts of the code. I.e., something that reinforces the

ephemerality and feels more like Wite-Out, or Post-its hovering "on top" of

your otherwise untainted code.

This sort of thing could also be made general enough that in-IDE breakpoints

could be implemented in terms of a code overlay.

These would ideally be represented visually within the IDE, but there'd be a

universally understood way to serialize them to text, in case you actually

wanted to process them to be turned into a real patch. If represented

conceptually, your editor should still give you the ability to toggle between

the visual-conceptual form and the "raw" text form, if you want.

- Raw form would be something inspired by the unified diff/patch format

- but only one line of context, and only one (or no) other line for prologue

- the context line is what gets marked up instead of the insertion

- with

= prepended to the line you're "pinning" to

- inserted lines wouldn't have any prefix except for whitespace, for

readability and copy-and-pastability

The best part is that there could be tight integration with editor's debugging

facilities. So when entering debug mode, what it's really doing is applying

these overlays to the underlying file, doing a new build with these in place,

and then running it. If the build tool is completely integrated into the IDE,

then the modified version of the source tree (i.e. with the overlays applied)

would never even get written to disk.

In essence, these would be ephemeral micro patchsets managed by editor itself

and not the source control system.

DSLs

Domain-specific languages (DSLs) are bad. They're the quintessential example

of a "now you have two problems" sort of idea. And that's not even a

metaphor; the popular quip is about the syntax of regular expressions—it's a

direct application of the more general form I'm pushing here.

The sentiment I'm going for isn't too far off from Robert O'Callahan's

thoughts about The Costs Of Programming Language Fragmentation, either.

Wikipedia Name System

Wikipedia Name System as a replacement for EV certificates

- See Extended Validation Is Broken

- Delegate to Wikipedia's knowledge graph to make the correct domain–identity

link

- Not as trivially compromised as it sounds like it would be; could be faked

with (inevitably short-lived) edits, but temporality can't be faked

- If a system were rolled out tomorrow, nothing that happens after rollout

that would alter the fact that for the last N years, Wikipedia

has understood that the website for Facebook is facebook.com

- Newly created, low-traffic articles and short-lived edits would fail the

trust threshold

- After rollout, there would be increased attention to make sure that

longstanding edits getting in that misrepresent the link between domain

and identity

- Would-be attackers would be discouraged to the point of not even trying

by Colby Russell. 2019 May 14.

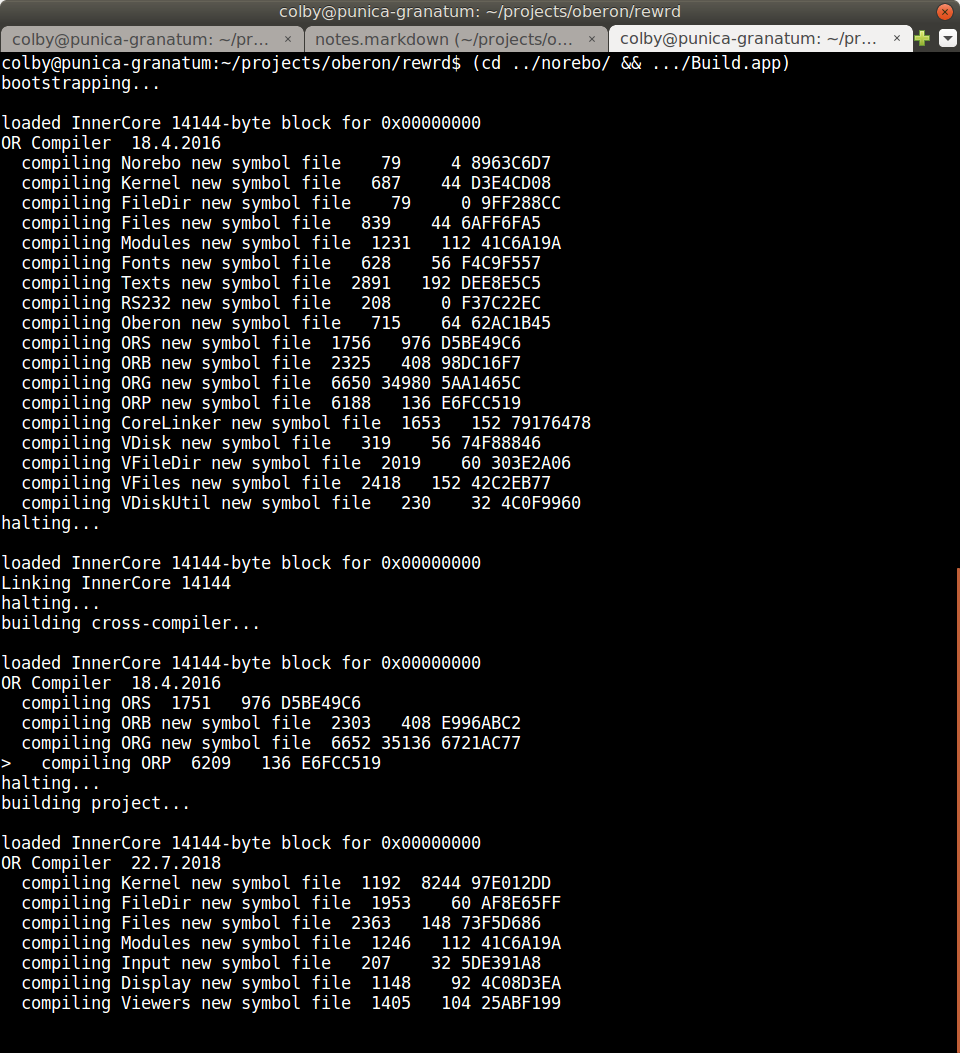

I encountered some issues during the development of TeroBuild/Terobo. This

post discusses how I handled those issues.

Terobo is a replacement for a small runtime called Norebo written by Peter

De Wachter. Norebo was originally implemented in C, and its purpose is to act

as a bridge from a host system (i.e., your computer) into the world that

Wirth's Oberon system expects to inhabit, by simulating it. That means

simulating the instruction set of the bespoke RISC design that Wirth cooked

up, plus a handful of system calls (or "sysreqs") to interact with the outside

world on the host machine.

Under Terobo or Norebo, when an Oberon program uses the Files.Seek or

Files.Write APIs within the system, the bridge on the inside of the system

relies on the machine code executing no differently than the CPU embodied in

real world hardware would, up to and including the branch instruction that

jumps from the calling code into subroutine being called. The Norebo bridge

at this point, however, attempts to write to a very large memory address:

something like 0xFFFFFFFC, or -4 if the bit pattern is interpreted as a 32-bit

two's complement signed integer. Since the hardware being emulated has

nowhere near 2^32 (4GiB) of memory, this address space is reserved for

memory-mapped IO, and it's known that this address in particular is used for

making sysreq calls.

Both Terobo and Norebo, simulating the hardware in question, know to intercept

reads and writes in this address space and handle them accordingly. For

example, the runtimes associate a Files.Seek request with the constant 15.

When a machine-level store instruction attempts to write the value 15 to

0xFFFFFFFC, the runtime delegates to an equivalent operation on the side of

the bridge rooted in the host system. Otherwise, Terobo is very much

concerned only with the fetch/decode/execute cycle present in anything dealing

with machine-level instructions. This can pose some problems, especially when

it happens on such an obscure platform.

Terobo is using a special build of the Oberon system crafted specifically to

operate non-interactively, with no peripherals to provide input and output for

the system, making diagnosis difficult when a problem rears its head, given

how opaque this works out to be. Disregarding that, the debugging situation

even within a full-fledged Oberon system is basically non-existent. Despite

the language being an ostensibly "safe" one, Oberon programs—especially the

system-level modules that get much of the CPU time within Terobo and

Norebo—are perfectly capable of and prone to doing the sorts of things

commonly associated with a language like C, such as branching into the void,

otherwise dereferencing a bad pointer, or getting caught in an infinite loop,

all because, say, my Files API implementation for Terobo is buggy.

So aside from writing perfect code on the first pass, how does one deal with

this?

For one, Peter's implementation in C already existed, which was helpful as an

overall guide, but not in fixing implementation-specific problems in the code

I was writing. (Side note: I'm not a fan of the buffer and typed array design

that TC-39 came up with for working with binary data. I find it really

cumbersome, and it's fraught with gotchas. For all its problems, I think the

way C exposes this kind of stuff to the programmer, if you consider language

design as a sort of UI, to be better, even with the proliferation of

pointers and the perils of using arithmetic for them.)

Secondly, I'd already begun working on my own interactive gdb-like debugger to

operate at the machine-level, allowing you to pause execution by setting

breakpoints, peek and poke at memory addresses, disassemble blocks of

instructions, and step through execution. Since the debugger fully controlled

the machine simulation, I'd even implemented reversible debugging so you could

step backwards through code. It's on this basis that I began working on

Terobo. Rather than starting from a blank slate, I just forked my debugger

(called rewrd), and began patching it in the general direction of Norebo,

implementing Peter's design for the special memory mapping scheme I explained

earlier.

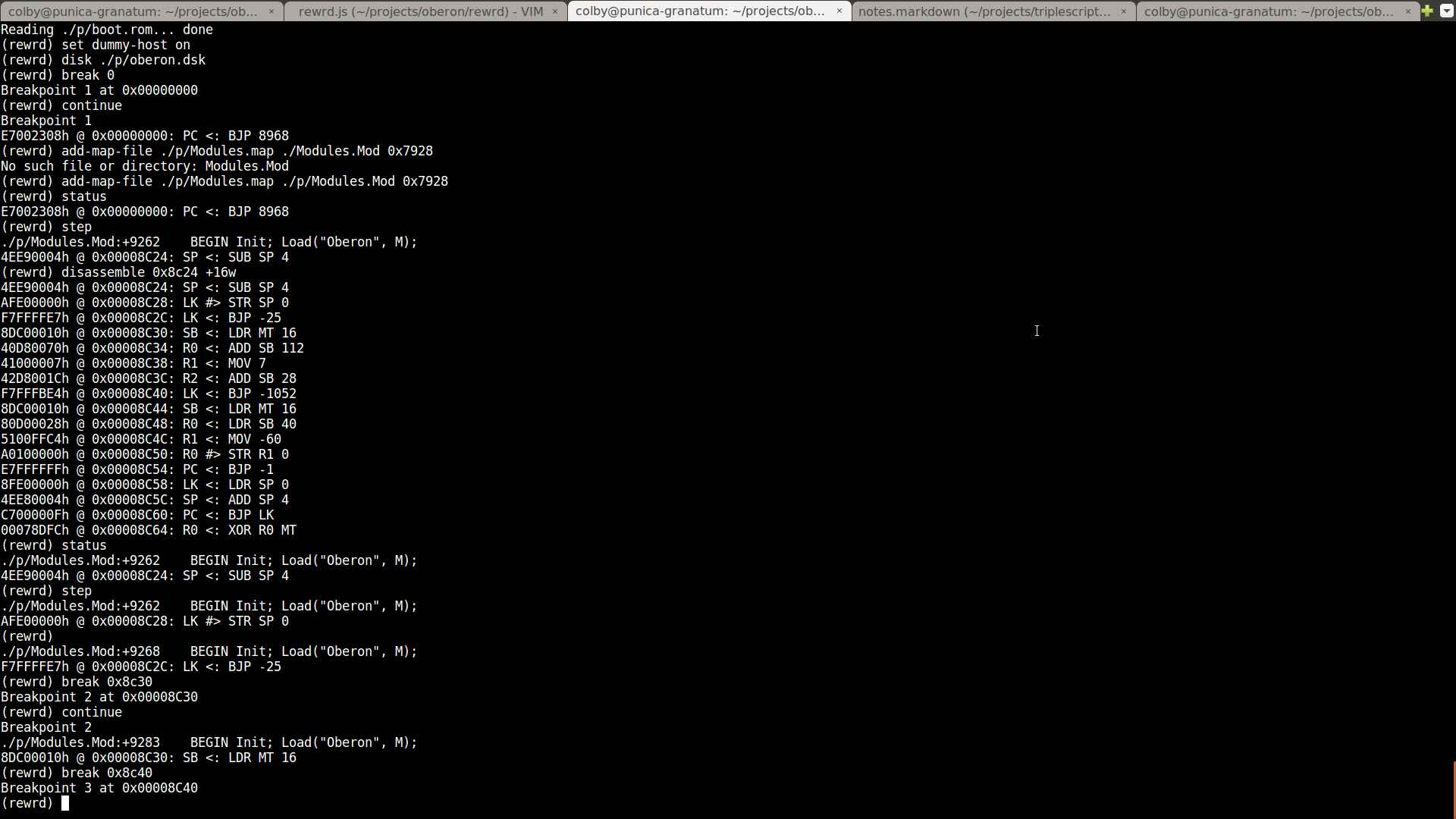

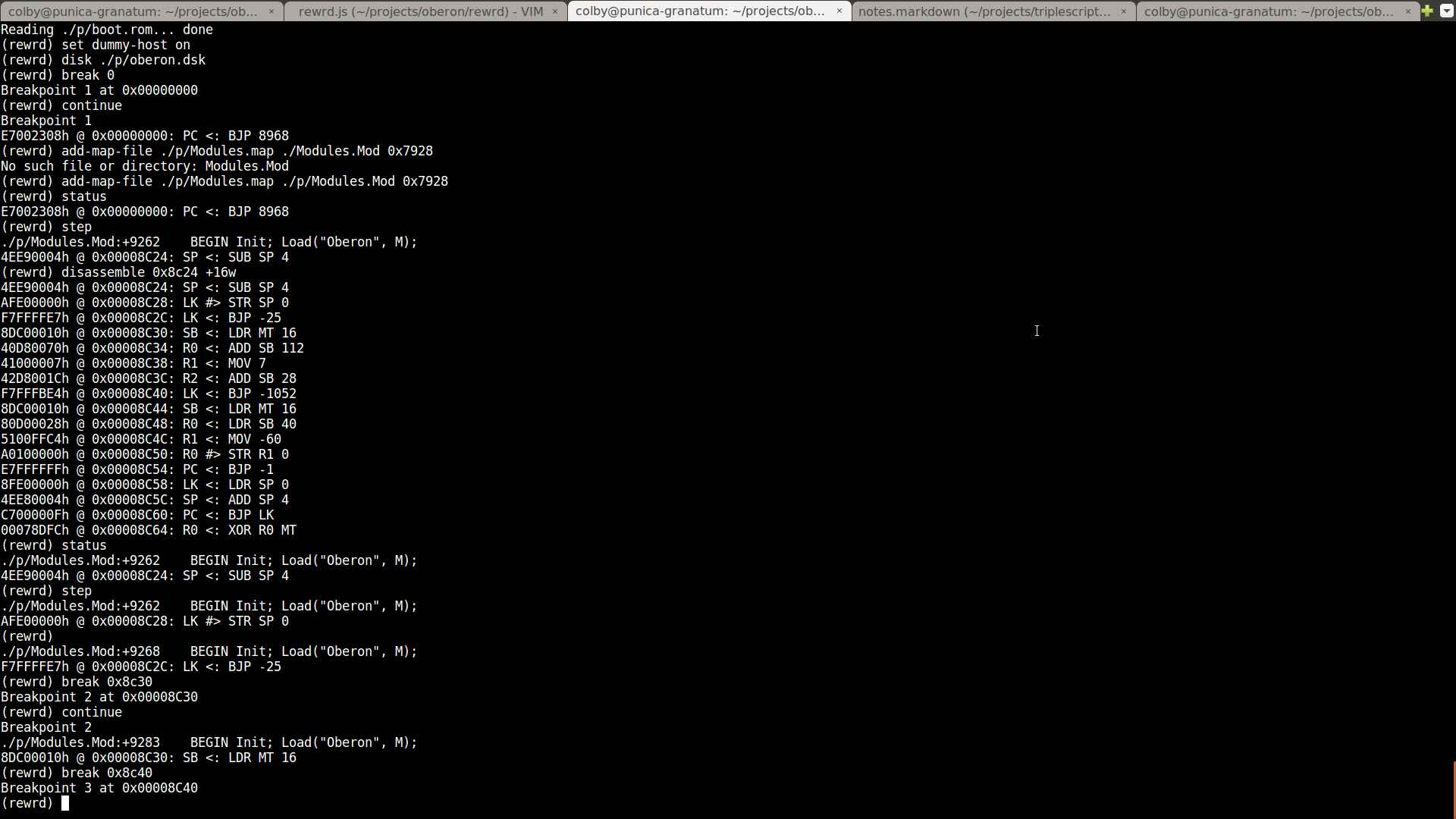

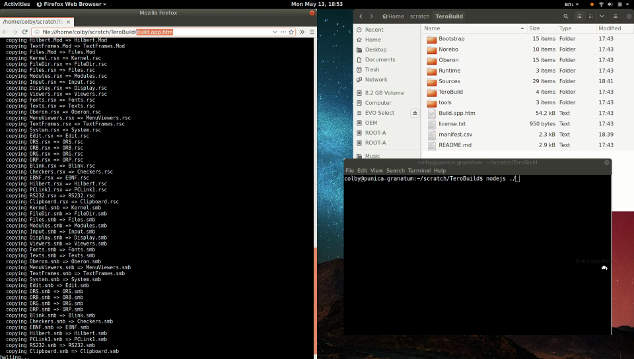

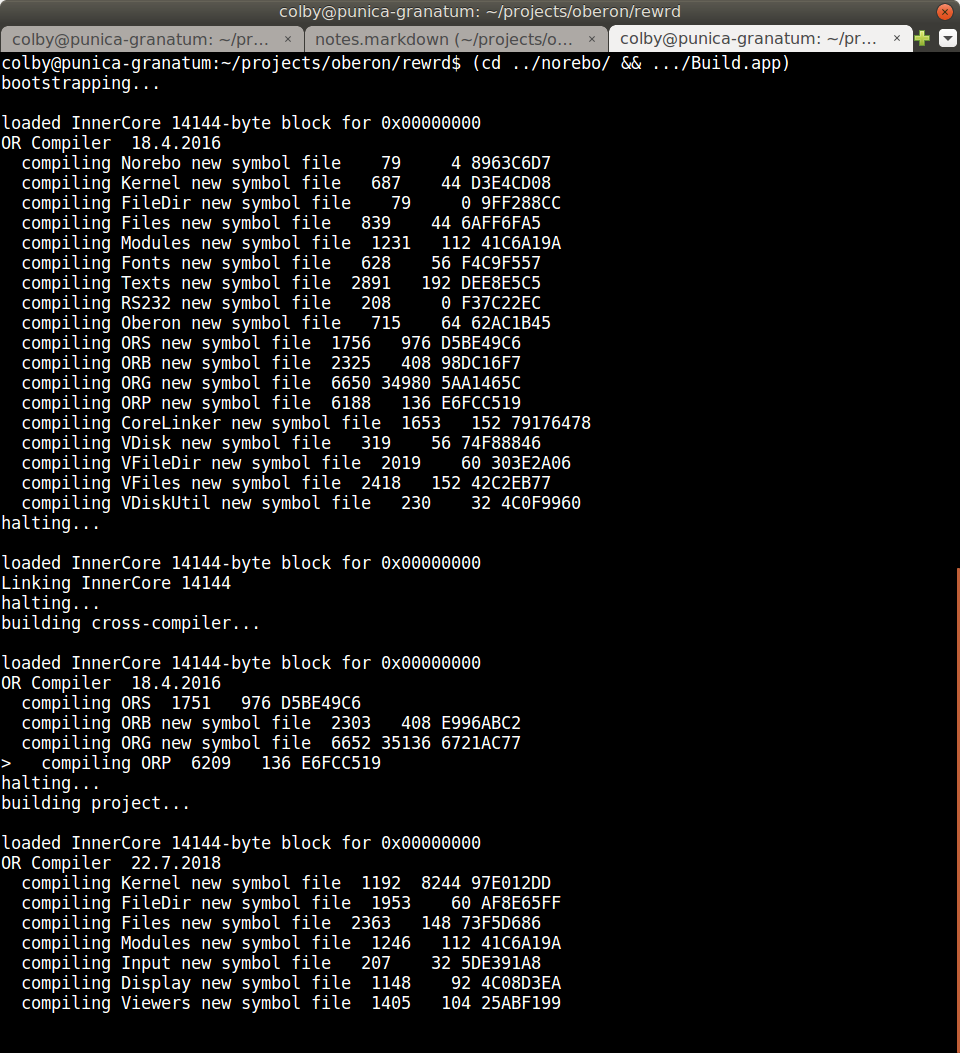

Here's a look at rewrd in action:

Occasionally, while developing Terobo, there would be problems that I had no

idea how to solve, due to how difficult it was trying to peer into a machine

operating so opaquely and where you had no bearings. I did already have

support for importing source maps to follow an arbitrary machine instruction

back to the original line of Oberon source code that was responsible for the

position in the current stack frame, although I didn't have any such maps on

hand for the binaries distributed in the Norebo directory. Generating them

would have been and still is a fairly cumbersome process, and finding out

which blocks of memory they mapped to would be something like an order of

magnitude even harder than that. I'd also already added a way to produce

something akin to core dumps, but this wasn't particularly useful given the

absence of any other tools that could process these dumps and communicate

anything meaningful about what they'd contain.

Two things that proved invaluable were adding tracing to both my

implementation and the C implementation, and I added memory dumps as well. I

patched the C implementation to take command-line flags to enable tracing,

limit the number of steps the simulated machine would take before halting, or

limit the number of memory-mapped sysreq invocations to handle, and upon

reaching the limit, immediately dump the machine's memory to disk, along with

the binary log containing the execution trace.

I implemented tracing very simply: every time the machine executed an

instruction, it would log the memory address of the instruction in question,

along with four bytes containing the instruction itself. Based on this, and

the same mechanism implemented in Terobo, I could take these traces, convert

them into human readable text files using a pipeline, and then diff them, all

with tools from the standard UNIX toolbox.

Here's the magic pipeline I used:

od -v -A n -t x4 .../terobo_trace | sed \

"s/\([^ ]\+\) \([^ ]\+\) /\1 \2\n /"

I was pretty bummed when I checked the man pages for od and didn't find any

way to force it to output to two columns (for two four-byte fields) instead of

four columns (for 16 bytes per row of output). The sed transformation fixes

this, although it can be somewhat slow for very large trace logs—I didn't feel

like stopping to write the code to do my own text conversion, though, even

though I should have.

Given two textual trace logs, one from my implementation and one from Norebo,

the line offset where diff reported a disparity may or may not be the

offending instruction. It's possible that due to a bad sysreq implementation

of some earlier call, the machine was ending up in a bad state but in such a

way it wasn't apparent by looking solely at the execution trace. So having

narrowed down a place where a problem was known to occur, I then turned to

looking at memory.

If some difference was apparent between Norebo and Terobo's traces at step N,

I'd take snapshots of the contents of memory there (only 8MB—up from the 1MB that

Oberon ordinarily runs under), and look at how the two compared. I'd then

establish the existence of some prior state where the two implementations

agreed, and work my way towards the problem area using the familiar process of

bisection. It was reasonable, though, to expect in most cases that any given

problem that occurred was a result of the implementation for the previous

sysreq.

And that's essentially it for half the bugs that I spent my time on.

Of the other half, they turned out being problems either in how I was dealing

with asynchronous file reads and attempting to re-enter the

fetch/decode/execute loop, or the poor way I'd hacked Terobo on top of rewrd's

debugger repl. The debugger ended up being very useful, however.

Even without the class of bugs that wouldn't have occurred had I not decided

to start off with rewrd forming the initial basis of the implementation, I'm

not sure how much longer development would have taken if I'd not had the

interactive debugging shell available. Additionally, I ended up fixing a

number bugs and adding features to rewrd as a result of my needs developing

Terobo, so there came some other good out of it.

Here, now, is a link (above) to a 2 minute video demonstrating the utility of

this work—extremely portable build tooling with no dependencies other than the

universally accessible application runtime.

by Colby Russell. 2019 May 10.

Project Norebo is a build tool for building/bootstrapping Wirth's Project

Oberon 2013.

If you're not familiar with Oberon-the-system or Oberon-the-language, know

that Project Oberon 2013 itself is a small, single user operating system

written in the Oberon programming language, that the latter is a major

inspiration for Go (cf Griessemer and Pike), and that the UI for the

latter—the Oberon system—even inspired the acme shell Rob Pike created for

Plan 9 at Bell Labs, which Russ Cox demonstrates here in the video of A Tour

of the Acme Editor.

Back to Norebo and then the showcase for this post: Terobo.

Project Norebo, as Peter de Wachter explains in the README, is a hack for

cross-compiling Project Oberon. The standard Oberon compiler is itself written

in the Oberon language, which means you'll need some other Oberon compiler to

build it. What's more, though, is that existing binaries come in the form of

object files that expect to run within the Oberon system—or at least inside

something implementing the Oberon system interfaces.

So not only are we faced with the classic bootstrapping problem for

self-hosted compilers, but the trough of despair descends one layer deeper

than that:

We want to compile Project Oberon, so

We want to run the Oberon compiler, so

We want to compile the Oberon compiler, so

We want to run the Project Oberon system.

This is where Project Norebo comes into play. It's meant both to bootstrap

the compiler and to build the Oberon system from source, emitting a disk image

that can run on the Oberon RISC emulator. Norebo is implemented partly in

Python for the high-level build steps, partly in C for the native runtime that

allows UNIX-like systems to emulate both the Oberon hardware and the core

Oberon system APIs, and partly in the Oberon language as a bridge to the C

runtime from within a locally hacked version of the Oberon system meant to run

embedded on the aforementioned C runtime.

This is fine if you have a C compiler, the right Python installed, and if your

system is otherwise sufficiently close to match the (possibly unknown) latent

assumptions that need to be satisfied in order for the build to go off without

a hitch.

Or, as Joe Armstrong relates in a similar anecdote:

So I Googled a bit and I found a project that said you can make nice

slide shows in HTML and they can produce decent PDF. And so I

downloaded this program, and I followed the instructions, and it said

I didn't have grunt installed! […] So I Googled a bit, and I found out

what grunt was. Grunt's—I still don't really know what it is, but...

[Then] I downloaded this thing, and I installed grunt, and it said

grunt was installed, and then I ran the script that was gonna make my

slides... and it said "Unable to find local grunt"[…]

Since Oberon is a small system, we should be able to achieve our build goals

from virtually anywhere, Python or no Python. As it turns out, we can do

better. Here's a preview:

Terobo and TeroBuild are together a re-implementation of Project Norebo's

C-and-Python infrastructure, respectively, but written in the triple script

dialect instead. As a triple script, this gives us deterministic builds

through Terobo, which is pretty much guaranteed to run on any consumer-grade

computer, regardless of what process a person is (or isn't) willing to go

through to make sure the right toolchain is set up beforehand. This is

because triple scripts require no special toolchain be set up—not even

something that seems as pedestrian (or "standard") as /usr/bin/python or a C

compiler. A triple script is its own toolchain. In other words, the repo

is the IDE.

Neither Terobo, Norebo, or anything involving Oberon is the real focus here.

This is personal milestone and a demonstration of the power behind the

philosophy of triple scripts, more than anything else.

Stay tuned for more developments related to triplescripts.org. The latter has

been my main side project for the better part of a year, and even though I

missed the anticipated launch in the early part of this year—due to long

illness and then, subsequent to that, a car accident—I'm going to continue

plugging away. I truly expect triplescripts.org to become kind of a Big Deal

and, as I've characterized it in the past, to end up winning if for no other

reason than through sheer tenacity and the convenience it will afford both

software maintainers and potential contributors alike.

Further viewing/reading:

by Colby Russell. 2019 March 6.

JS has gotten everywhere. It drives the UI of most of the apps created to run

on the most accessible platform in the world (the web browser). It has

been uplifted into Node and Electron for widespread use on the backend, on the

command-line, and on the desktop. It's also being used for mobile development

and to script IOT devices, too.

So how did we get here? Let's review history, do some programmer

anthropology, and speculate about some sociological factors.

JS's birth and (slightly delayed) ascent begins roughly contemporaneous with

its namesake—Java. Java, too, has managed to go many places. In the HN

comments section in response to a recent look back at a 2009 article in IEEE

Spectrum titled "Java’s Forgotten Forebear", user tapanjk writes:

Java is popular [because] it was the easiest language to start with

https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=18691584

In the early 2000s in particular, this meant that you could expect to find

tons of budding programmers adopting Java on university campuses, owing to

Sun's intense campaign to market the language as a fixture in many schools' CS

programs. Also around this time, you could expect its runtime—the JRE—to be

already installed on upwards of 90% of prospective users' machines. This was

true even when the systems running those machines were diverse. There was a

(not widely acknowledged) snag to this, though:

As a programmer, you still had to download the authoring tools necessary for

doing the development itself. So while the JRE's prevalence meant that it was

probably already present on your own machine (in addition to those of your

users), its SDK was not. The result is that Java had a non-zero initial setup

cost for authoring even the most trivial program before you could get it up

and running and putting its results on display.

Sidestepping this problem is where JS succeeded.

HTML and JS—in contrast to not just Java, but most mainstream programming

tools—were able to drive the setup cost down to zero. When desktop operating

systems were still the default mode of computing, you could immediately go

from non-developer to developer without downloading, configuring, or otherwise

wrangling any kind of SDK. This meant that in addition to being able to

test the resulting code anywhere (by virtue of a free browser preinstalled

on upwards of 97% of consumer and business desktops), you could also get

started writing that code without ever really needing anything besides what

your computer came with out of the box.

You might think that the contemporary JS dev ecosystem would leverage

this—having started out on good footing and then having a couple decades to

improve upon it. But weirdly, it doesn't work like that.

JS development today is, by far, dominated by the NodeJS/NPM platform and

programming style. There's evidence that some people don't even distinguish

between the NodeJS ecosytem and JS development more generally. For many, JS

development probably is the NodeJS ecosystem and the NodeJS programming

style is therefore seen as intrinsic to the way and form of JS.

In the NodeJS world, developers working in this mindest have abandoned one of

the original strengths of the JS + browser combo and more or less replicated

the same setup experience that you deal with on any other platform. Developer

tunnel vision might trick a subset of the developers who work in this space

into thinking that this isn't true, but the reality is that for NPM-driven

development in 2019, it is. Let's take a look. We'll begin with rough

outline of a problem/goal, and observe how we expect to have to proceed.

Suppose there's a program you use and you want to make changes to it. It's

written for platform X.

With most languages that position themselves for general purpose development,

you'll start out needing to work through an "implicit step 0", as outlined

above in the Java case study. It involves downloading an SDK (even if that's

not what it's called in those circles), which includes the necessary dev tools

and/or maybe a runtime (subject to the implementation details of that

platform).

After finding out where to download the SDK and then doing exactly that, you

might then spend anywhere from a few seconds or minutes to what might turn out

to be a few days wrestling with it before it's set up for your use. You might

then try to get a simple "hello, world"-style program on the screen, or you

might skip that and dive straight into working on the code for the program

that you want to change.

Contemporary JS development really doesn't look all that different from this

picture—even if the task at hand is to do "frontend" work meant to run in the

browser—which was the predominant use of JS early in its lifetime, when it

still did have zero setup cost.

I have a theory that most people conceptualize progress as this monotonically

increasing curve over time, but progress is actually punctuated. It's

discrete. And the world even tolerates regress in this curve. If engaged

directly on this point, we'd probably find that for the most part any given

person will readily acknowledge that this is the true character of that curve,

but when observed from afar we'll see that most are more likely to appear as

if in a continual motte-and-bailey situation with themselves—that their

thoughts and actions more closely resemble that of a person who buys into the

distorted version of progress, despite the ready admission of the contrary.

Steve Klabnik recently covered the idea of discrete and punctuated progress

in his writeup about leaving Mozilla:

at each stage of a company’s growth, they have different needs. Those needs

generally require different skills. What he enjoyed, and what he had the

skills to do, was to take a tiny company and make it medium sized. Once a

company was at that stage of growth, he was less interested and less good at

taking them from there.

https://words.steveklabnik.com/thank-u-next

The corollary to Steve's boss's observation is that there's stuff (people,

practices, et cetera) present in later phases and to which we can directly

attribute the success and growth during that phase, but that these things

could have or would have doomed the earlier phases. It seems that this is

obviously true for things like platforms and language ecosystems and not just

companies.

To reiterate: JS's inherent zero-cost setup was really helpful in the

mid-to-late 2000s. That was its initial foot in the door, and it was

instrumental in helping JS reach critical mass. But that property hasn't

carried over into the phase where devs have graduated to working on more

complex projects, because as the projects have grown in complexity, the

tooling and setup requirements have grown, too.

So JS, where it had zero setup costs before, now has them for any

moderate-to-large-scale project. And the culture has changed such that its

people are now treating even the small projects the same as the complex

ones—the first thing a prospective developer trying to "learn to code" with JS

will encounter is the need to get past the initial step zero—for "setting up a

development environment". (This will take the form of explicit instructions

if the aspiring developer is lucky enough to catch the ecosystem at the right

time and maybe with the help of a decent mentor, or if the aspiring developer

is unlucky and the wind isn't blowing in a particularly helpful way, then it

may be an implicit assumption that they will manage to figure things out.)

And developers who have experience working on projects at the upper end of the

complexity spectrum also end up dealing with the baggage of implicit step zero

for their own small projects—usually because they've already been through

setup and are hedging with respect to a possible future where the small

project grows wildly successful and YAGNI loses to the principle of PGNI

(probably gonna needed it).

Jamie Brandon in 2014 gave some coverage to this phenomenon on the Light Table

Blog (albeit from the perspective of Clojure) in a post titled "Pain We

Forgot".

To pull an example from the world of JS, let's look at the create-react-app

README, which tells you to run the commands:

npx create-react-app my-app

cd my-app

npm start

What assumptions does it make? First, that you're willing to, able to, and

already have downloaded and installed NodeJS/NPM to your system; secondly,

that you've gone through the process of actually running npm install

create-react-app, and that you've waited for it to complete successfully.

(You might interject to say that I'm being overly critical here—that by the

time you're looking at this README, then you're well past this point.

That's the developer tunnel vision I referred to earlier.)

Additionally I'll note that if we suppose that you've started from little more

than a blank slate (with a stock computer + NodeJS/NPM installed), then

creating a "hello, world" app by running the following command:

npm install create-react-app && npx create-react-app foo

... will cost you around 1.5 minutes (in the best cases) while you wait for

the network and around half a GB of disk space.

If JS's early success in the numbers game is largely a result of a strength

that once existed but is now effectively regarded as non-existent, does that

open up the opportunity for another platform to gobble up some easy numbers

and bootstrap its way to critical mass?

Non-JS, JS-like languages like Haxe and Dart have been around for a while and

are at least pretending to present themselves as contenders, vying for similar

goals (and beyond) as what JS is being used for today. And then there are

languages nothing like JS, like Lua, which has always touted its simplicity.

And then there is the massive long-tail of other languages not named here (and

that possibly haven't even been designed and implemented yet).

What could a successful strategy look like for a language that aimed to

displace JS?

- Skips the problems with contemporary JS development

- no implicit or explicit initial setup required

- avoids problems that have been referred to as "JS fatigue"

- Plays to JS's original strengths

- stupidly easy to go from zero to "hello world"

- insanely huge installed base

If you come from a JS background, you might argue that you still have the

option of foregoing all the frameworks and tooling which have obviated JS's

zero setup strength. As I alluded to before, though: rarely does anyone

actually run a project like that. So while "hello, world" is still

theoretically easy, the problem is twofold:

The "hello, world" lessons that learners have in front of them and that are

pushed the most are more likely to be similar to the ones for

create-react-app

While you can do your own thing, virtually no one today is going to clone an

existing project and find anything other than the sorts of things I've

described

Which is to say, that in either case as a developer, you're going to run into

this stuff, because it's what people are pushing in this corner of the world.

And therefore the door is wide open for a contender to disrupt things.

So the question is whether it's possible to contrive a system (a term I'll use

to loosely refer to something involving a language, an environment, and a set

of practices) built around the core value that zero-cost setup is

important—even if the BDFL and key players only maintain that stance up to the

point where the ecosystem has reached a similar place as contemporary JS in

its development arc. Past this point, it would be a free option to abandon

that philosophy, or—in order to protect the ecosystem from disruption by

others—to maintain it. It would be smart for someone with these ambitions to

shoot for the latter option from the beginning and take the appropriate steps

early to maintain continuity through all its phases, rather than having to

bend and make the same compromises that JS has.

I didn't set out when writing this post to offer any solutions or point to any

existing system, as if to say, "that's the one!". The main goal here is to

identify problems and opportunities and posit, Feynman-style (cf There's

Plenty of Room at the Bottom), that there's low-hanging fruit here, money

on the table, etc.

by Colby Russell. 2019 February 15.

Unlaunched

Last summer, I began work on a collection of projects with a common theme.

The public face of those efforts was and is meant to be triplescripts.org.

But wait, if you type that into the address bar, it's empty. (If you're

reading from the future, here's an archive.org link of the triplescripts

front page as it existed today.) So what's the deal?

In December, I set the triplescripts.org launch date for January 7. This

has been work that I'm genuinely excited about, so I was happy to have a date

locked down for me to unveil it. (Although, as I mentioned on Fritter, I've

been anticipating that it will succeed through tenacity—a slow burn, rather

than an immediate smash hit.)

Starting in the final week before that date, a bunch of real life occurrences

came along that ended up completely wrecking my routine. Among these—and the

main thing that is still the most relevant issue as I write this now—is that

I managed to get sick three times. That's three distinct periods with three

different sets of symptoms, and separate, unambiguous (but brief) recoveries

in between. So it's now a month and a week after the date I had set for

launch, and triplescripts.org has no better face than the blurby,

not-even-a-landing-page that I dumped there a few months back, and these ups

and downs have me fairly deflated. Oh well for now. Slow burn.

Unloading a month's thoughts

The title of this post is a reference to Nadia Eghbal's monthly newsletter,

which has been appearing in the inbox under the title "Things that happened

in $MONTH". I like that. Note, in case you're misled by bad

inference on the title, that the newsletter is about ideas, not

autobiographical details.

I've seen some public resolutions, or references to resolutions by others, to

publish more on personal sites and blogs in 2019 (such as this Tedium article

on blogging in 2019). I don't make New Year's resolutions, so I was not

among them. But I like the tone, scope, and monthly cadence in the idea

behind "Things that happened". So on that note alone—and not motivated by a

tradition of making empty promises for positive change when a new year

begins—I think I will commit to a new outlook and set of practices about

writing that follows in the vein of that newsletter.

The idea is to publish once a month, at minimum, everything that I considered

that month as having been "in need of a good writeup", and to do so regardless

of the state it's actually reaches by the end of the month—so something on the

topic will go out even if it never made it to draft phase. Like continuous

integration for written thought.

Although when you think about it, what's with all the self-promises, of,

you know, writing up a thorough exegesis on your topic in the first place?

Overwhelming public sentiment is that there's too much longform content. As

even the admirable and respectable Matt Baer of write.as

put it, "Journalism isn't dead, it just takes too damn long to read." (Keep

in mind this is from the mouth (hand) of a man whose main business endeavor at

the moment hinges on convincing people to write more.) And this is what

everyone keeps saying is the value proposition of Twitter, anyway, right?

High signal, low commitment, and low risk that you'll end up snoring.

Ideas are what matter, not personal timelines. I mentioned above that

Nadia's newsletter is light on autobiographical details, as it should be.

Sometimes I see that people aren't inspired to elaborate on any particular

thought, but find themselves in a context where they're writing—maybe as a

result of some feeling of obligation—so they settle into relaying information

about how they've spent themselves over some given time period—information

that even their future self offset a couple months down the line wouldn't find

interesting. So these monthly integration dumps will remain light on

autobiographical details, except in circumstances where those details fulfill

some supporting role to set the scene or otherwise better explain the idea

that's in focus.

Unlinked identity

I'm opposed to life logs in general. I hate GitHub contribution graphs, for

example, because they're just a minor variation of the public timeline concept

from any social network, and I've always disliked those. This is one reason I

never fully got on board with Keybase.

Keybase's social proofs are pretty neat, the addressing based on them is even

neater, and in general I feel some goodwill and positive thought toward what I

perceived as Keybase's aspirations towards some sort of yet-to-be-defined

integration point as your identity provider. But I realized a thing a few

months after finally signing up for Keybase, which is that their

implementation violates a personal rule of mine: participation in online

communities originates from unlinked identities, always.

When I was throwing my energy into Mozilla (and Mozilla was throwing its

weight in the direction of ideals it purported to be working for), Facebook

Connect was the big evil. The notion that the way to participate—or, as in

the worst cases, even just to consume—could happen only if you agreed to "Sign

in with Facebook" (and later, with Google; nowadays it's Twitter and GitHub),

was a thing unconscionable. BrowserID clearly lost, but the arguments

underpinning its creation and existence in the first place are still valid.

I'm not sold by the pitch of helping me remember how I spend my time. I'm not

interested in the flavor of navelgazing that you get from social networks

giving you a look back at yourself N months or years down the line.

And we should all be much less interested, further still, in the way that most

social networks' main goal is to broadcast those things to help others get

that kind of a look at you, too.

Look at it like this: if you and I work together—or something like that—then

that's fine. You know? That's the context we share. If I go buy groceries

or do something out in public and we happen run into each other, that would be

fine, too. But if one of my coworkers sat outside my place to record my

comings and goings, and then publicized that info to be passively consumed by

basically anyone who asked for it, then that would not be okay.

My point is, I like the same thing online. If I'm contributing to a project,

for example, I'm happy to do so with my real name. If you're in that circle

(or even just lurking there) and as a result of some related interest you run

into my name in some other venue, then, hey, happy coincidence. But I'm less

interested in giving the world a means to click through to my profile and find

a top-level index of my activity—and that's true without any desire to hide my

activity or, say, my politics, as I've seen in some cases. After all, if that

were the goal, it would be much easier just to use a pseudonym.

So I say this as a person with profoundly uninteresting comings and goings—

but I realize that giving coverage to this topic from this angle will probably

trigger the "what are you trying to hide?" reflex. Like I said, I use my real

name. My email address and cell phone number are right there in the middle of

the colbyrussell.com landing page, which is more than you can say for most

people. (I've mentioned before how weird it is that 25 years ago, you could

look anyone up in the phonebook, but today having something like that

available seems really intrusive.) Besides, not even the Keybase folks

themselves buy the pitch; at this time, the most recent post to their company

blog is the introduction of Keybase Exploding Messages. And Snapchat's

initial popularity says something about how much the general public truly

feels about the value of privacy, despite how often the "if you have nothing

to hide…" argument shows up.

So in the case of Keybase, keep the social proofs and keep the convenient

methods of addressing, but also keep all those proofs and identities

unlinked. I don't need a profile. Just let me create the proofs, the same

principle in play when I prove everywhere else online that I control the email

I used to sign up, but it need not tie into anything larger than that single

connection. Just let my client manage all the rest, locally.

Unacknowledged un-

Sometimes an adage is trotted out that goes roughly like this:

Welp, it's not perfect, but it's better than nothing!

And sometimes that's true. It's at least widely understood to be true, I

think.

What I don't see mentioned, ever, is that sometimes "it's better than nothing"

is really, really not true. In some cases, something is worse than nothing.

My argument:

Voids are useful, because when they exist you can point to them and trivially

get people to acknowledge that they exist. There's something missing. A bad

fix for a real problem, though, takes away the one good thing about a void.

For example, consider a fundraising group that (ostensibly) exists to work on

a solution towards some cause—something widely accepted to be a real problem.

Now consider if, since first conception, and in the years intervening, it's

more or less provable that the group is not actually doing any work to those

ends, or at least not doing very good work when measured against some rubric.

Briefly: we could say that the org is some measure of incompetent and/or

ineffective.

The problem now is that our hypothetical organization's mere existence is

sucking all the air out of the room and hampering anyone who might come along

and actually change things.

That is, even though we can argue rationally that their activity is equivalent

to a void, it's actually worse than a void, since—once again—you can point

to voids and say, "Look, we really need to do something about this!", but it's

harder to do that here. Say something about the underlying problem—the one

that the org was meant to solve—and you'll get railroaded in the direction of

the org.

So these phenomena are a sort of higher order void. They're equivalent with

respect to their total lack of contribution to forward progress on the issue

we care about, but then what they also do is disguise their existence and act

like sinks, so not even the potential energy stored nearby never gets put to

effective use.

Underdeveloped

Other stuff from January that requires coverage here, but doesn't exist in

longform:

I had an animated conversation with my friend that what the United States

and the world in general really needs in order to adopt the metric system is

to use the "metric hand" as the de facto human scale reference unit to fill

the void created by the deprecation and displacement of the 12-inch foot.

Meters are too long, and centimeters are too short. ("How tall is that guy?

1.8 meters?" C'mon.) Spoiler alert: the metric hand (or just "hand" for

short) would be defined as 1 decimeter (10 cm). To easily convert between

hands and feet, approximate 1 decimeter as 4 inches, thus there are

approximately 3 hands in a foot. We say the proper term is the "metric

hand" to distinguish from the existing unit from the imperial system called

the "hand", which is exactly 4 inches, but also used essentially nowhere,

except in some equestrian circles. So there shouldn't be much confusion,

and even if there were, the figures would only be off by 1.8 mm, which is

tiny—and also not an approximation; that is, it's off by exactly 1.6 mm,

no rounding.

Zero-obligation communities could probably extract more value from their

contributors (including converting passive bystanders into contributors) by

fostering a culture of voluntoldism and getting maintainers to put in some

asks of their own. Right now, people are half-insisting that there's

something intrinsic to open source that is placing a high burden on

maintainers. Mostly, I regard this as the result of bad practices

originating from the culture of GitHub, not intrinsic to open source. But

either way, it's widely reported that maintainers are burning out. Users

are showing up and asking for too much. How about reversing polarity and

start conditioning maintainers into asking for things from users and less

involved contributors? The idea is for maintainers to give consideration to

the most effective way a project would benefit if it had at its disposal a

voluntary group of mechanical turks. These would be people willing to

execute the routines that the maintainers write with awareness and intention

of them being carried out in meatspace.

Resource-proportionate billing was back on my mind, and it seems like an

underutilized trick of consumer psychology. Recently I heard a creator

complaining of the absurdity that people will pay $5 every day for something

as trivial as coffee, but generally won't help fund the people creating the

things they like, even when its effect is greater than coffee. Few people

buy books (though some do). Fewer support intangible creative output. Now,

when you consider the tiny pool of those left, what those in the pool

usually want is to know is why you need money—what your expenses are. So

that's the complaint. Okay. Right. So leverage that. Approach it from

the other end and think of it not as the absurdity that it is but some

psychological effect that you can optimize for to convince people that

paying is worthwhile. I have more on this topic, but in the spirit of the

commitment, I'm disclosing my thoughts here in their rough form. As I wrote

before on Fritter: "Radical transparency about global costs as well as

the actual load caused by your individual account activity (down to the cost

for servicing a GET request) underpins the whole idea. Sandstorm's recent

changes (no more free accounts + numbers Kenton published after the switch

was flipped) are a good case study." I also think lower prices are key.

Lots of people are trying for $7–9/month, but that's more expensive than

paid email—and email is way more important than whatever you're probably

trying to charge for. This is another thing that I was happy to stumble

upon when looking at what write.as is doing. The lowest priced paid

option is $12 per year. And why not? $1/month at scale is certainly

enough to cover resource costs (where "the time of the people running the

thing" is rightly considered to be a resource, too).

Who should fund open source? Are companies to blame for being leeches? Why

not place the responsibility with the developers working at those companies

when they are leveraging others' work and converting it into increased stature

and personal wealth for themselves? When payday comes around, funds flow

from the corporation into the hands of its worker for making progress on his

or her assignment, but it generally stops there. Why do we treat this

differently than if you took on a project, used subcontractors to complete a

portion of the work, and then stiffed them? I understand the argument that

the "subcontractors" here were never promised anything, and that's at least

consistent. What's inconsistent, logically, is when I see people

introducing the idea that there's a problem with funding in open source

because companies are leeching from the fount of FOSSomeness and not giving

back. Where does the idea come from that it's the company's responsibility

to settle the debts involved? Programmer salaries are high—above the US

national average income for an entire household. To repeat: why aren't

the corporate programmers here being held responsible, rather than the

company in the abstract that happens to employ them? Jeff Kaufman exists

as an extreme example at the other end—a programmer "earning to give" and

willingly redistributing his pay, albeit not in a "compensate FOSS

subcontractors" style, but for reasons that fit under the familiar label of

"philanthropy".

by Colby Russell. 2018 October 11.

My "coming of age" story as a programmer is one where

Mozilla played a big part and came at a time before the

sort of neo-OSS era that GitHub ushered in. It's been a little over 5 years,

though, since I decided to wrap things up in my involvement and called it

quits on a Mozilla-oriented future for various reasons.

More recently—but still some time ago, compared to now—in a conversation

about what was wrong with the then-current state of Mozilla, I wrote out a

response with my thoughts but ultimately never sent it. Instead, it lingered

in my drafts. I'm posting it here now both because I was reminded of it a few

weeks ago from a very unsatisfying exchange with a developer still at Mozilla

when a post from his blog came across my radar, and because, as I say below,

it contains a useful elaboration on a general phenomenon not specific to

Mozilla, and I find it worthwhile to publish. I have edited it from the

original.

It should also be noted that the message ends on a somewhat anti-cynical note,

with the implication of a possibility left open for a brighter future, but the

reality is that the things that have gone on under the Mozilla banner since

then amount to a sort of gross shitshow—the kind of thing

jwz would call "brand necrophilia". So whatever residual

hope I had five years ago, or at the time I first tried to write this, is now

fairly far past gone, and the positivity sounds a little misplaced.

Nonetheless, here it is.

in-reply-to: [REDACTED]

First, Mozilla has been running on steam for years. What's going on with

Mozilla now is just the culmination of a bunch of bad decisionmaking that

has continued because the people helming the Corp had a long enough runway

that the negative feedback can't be pinned down irrefutably to anything in

particular.

It goes like this: you can do the wrong things but be in a long enough

feedback loop that the effects only really start to show themselves some time

later. So rather than successfully correlating results to their real

causes, what happens instead is:

a) people fool themselves in the meantime that bad things aren't bad, and

b) in the aftermath, when the consequences do start to appear, the temporal

offset from the real root cause is so large, and they have so many

other things to attribute failures to, that they can (and probably

will) go the intellectually dishonest route and pick the thing that is